The Beat Goes On, Part XX.

010. U-Roy “Dynamic Fashion Way”

(Ewart Beckford)

1969

Available on Super Boss: The Best of U-Roy

Jamaica is not a place where firsts can be ascertained with any reliability; history is in the eye of the reteller, and everyone gets their day in the sun. So calling this the first “toast” record is not only an exercise in futility, it’s pointless. And it wouldn’t matter anyway if it weren’t also a great record. Producer Keith Hudson conjures up a tinny, toy-carnival track, and the Originator just lets his id out. To be explicit, he raps. Not in any way that a thirteen-year-old 50 Cent fan would recognize, maybe (Jamaicans just aren’t that percussive, you know?), but it’s the trickle of water that will one day carve the Grand Canyon of the modern music world. It’s also very, very rasta dread roots reggae; the suits of rocksteady and the toothy smiles of ska are gone. Instead, it’s constantly-shifting patterns, a blurting MC, and unintelligibility. This way to the future.

009. The Who “My Generation”

(Pete Townshend)

1965

Available on My Generation

The bass solos, that’s why. Not Daltrey’s corny sputtering, or Moon’s clattering din, or — dear God — Townshend’s far-too-easily-mocked (especially in the 21st century) lyric. But Entwhistle’s solos, meaty and beaty and spazzing all over the song, making it punk a decade before punk was a twinkle in Lester Bangs’s eye. John was the normal one of the group; afflicted neither with Pete’s pseudo-artistic aspirations, Roger’s preening machismo, or Keith’s irresponsible lunacy, he stood there and played his bass, no matter how boring it got. And when the Who made their preening, pseudo-artistic, irresponsible Generational Statement, it was Entwhistle who both anchored it rhythmically and sent it spiralling into the noisy chaos that so much of the best music of later years would imitate.

008. Bob Dylan & Johnny Cash “Girl from the North Country”

(Bob Dylan)

1969

Available on Nashville Skyline

(Note: For bookkeeping purposes, I’m counting this as a Johnny Cash song. But otherwise, yes, it would be the sixth song on the list where Bob Dylan sings lead. What can I say?) Now, normally, this kind of thing shouldn’t work. Not only is it a cover of a song which was already drummed into the popular consciousness with Simon & Garfunkel’s ornately gorgeous “Canticle/Scarborough Fair,” but it’s an English folk song interpreted by quite possibly the two most American men on the planet. And it’s a supergroup of sorts, or at least a collaboration that one would expect to be more like Clive Davis producing Santana than a natural fit. But it is. Bobby’s reedy tenor and Johnny’s rumbling baritone twine, curl, and echo each other perfectly. It’s damn near the most beautiful thing either of them ever did. One of the high-water marks not only of folk music, but of all music past, present and future.

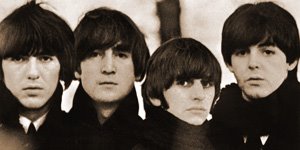

007. The Beatles “Here Comes the Sun”

(George Harrison)

1969

Available on Abbey Road

The Beatles were always ahead of the curve. (Okay, so they were behind the curve on musique concrète. Or . . . were they ahead of it on sampling?) That’s the thinking, anyway, and you can read the logic: first major beat group, first to write all their own music, first pop group to use arrangements from classical music, first to apply psychedelia to pop, first concept album, first to retrench with more roots-oriented music, first to break up . . . . (I’m not seriously suggesting they were actually the first in any of these. They were very good barometers, though.) But one of the underrecognized facts is that with their last album (sigh. Last-recorded, not last-released), they not only predicted the singer-songwriter soft rock that would dominate pop for the next five years, they did it better than anyone. Wait, who’s this they? I mean, of course, that George did.

006. The Ronettes “Walking in the Rain”

(Barry Mann/Phil Spector/Cynthia Weil)

1964

Available on The Best of the Ronettes

Lyrically, it recalls the Gershwins’ best non-show song, “The Man I Love,” in its dreamy evocation of how wonderful it’ll be once Ronnie finds the boy she wants to spend the rest of her life with. The fact that she was married already — and to her producer — and that he abused her — and that after leaving him she never really found a good platform for her intense pop presence (well, not yet) can only give us, who know how the story turns out, a frisson of cognitive dissonance. It’s not in the song. However cruel and psychotic a taskmaster Phil Spector might have been, he knew how to set his wife’s voice, as a great jeweler knows how to set a diamond, and the combination of harmonies, instrumentation, production, and even sound effects here screams teenage romanticism at its highest (virginal) peak.

005. The Beach Boys “Heroes and Villains”

(Van Dyke Parks/Brian Wilson)

1967

Available on Sounds of Summer: The Very Best of the Beach Boys

For years, it was the only charting song (besides “Good Vibrations,” which is its own separate monolith) that gave any clue to how wild and dense Smile would have been. And now that we have Smile — or, more cautiously, a version of Smile — it remains not just a high point of the album, but of the Boys’ career. It’s the Wild West, as filtered through Hollywood, through singing cowboys and Western soundtracks written by people who have never twanged in their lives. It’s a Wild West set, in fact, where the false storefronts hide false stores where you can only buy trinkets, and the guys in the white hats fight the guys in the black hats every two hours, all good clean fun, come on down, bring the children. It’s the Walt Disney version of American history, and an implicit criticism of it, and also just amazing to listen to for the density of the harmonic construction. Seriously.

004. Bob Dylan “Love Minus Zero/No Limit”

(Bob Dylan)

1965

Available on Bringing It All Back Home

It says something about Dylan at this period that his most lovely, simple, and elegant love song still contains a lyric like “in ceremonies of the horsemen, even the pawn must hold a grudge.” Is that about chess? Politics? Economic inequality in a militarist society? What on earth does it have to do with the beautiful, winning portrait of “my love”? Doesn’t matter, of course; half the reason to listen to Dylan in the mid-60s is the abstruse cascade of imagery. The other half is the heart-stopping beauty of the melody (yes, a real melody), the spare but shimmering guitar, and his voice. It’ll never be mistaken for Perry Como’s, but it contains worlds of tenderness and grace in its microtones.

003. Aretha Franklin “Respect”

(Otis Redding)

1967

Available on Lady Soul

Even after hearing it, at a conservative estimate, 5,000 times without going out of my way to do so. Even after hearing it punctuate the sudden appearance of any large black woman in a comedy for the past fifteen years. Even after seeing drunk white teenagers try to dance to it. It remains not just a cultural touchstone — we’ll always have plenty of those — or a personal favorite — I mean, really, who doesn’t love it? — but something even more incalculable: a coherent piece of art, the finest moment of the Stax/Volt crew (Booker T. & the MG’s, Isaac Hayes, the Sweet Inspirations), and the magic-in-a-bottle capturing perfectly, for all time, the unleashed force of Queen Aretha, the greatest female soul singer in the history of forever. It took me, at a conservative estimate, 2,500 listens to realize that it was not just a fragmented stream-of-consciousness thing, but that it had structure, verses, a chorus, everything. That’s the power of the Queen: so great you forget about the art and just listen to the pow.

002. Martha & the Vandellas “Dancing in the Street”

(Marvin Gaye/Ivy Hunter/William “Mickey” Stevenson)

1964

Available on The Ultimate Collection

There’s still a tightening in my chest every time I hear that opening horn riff. It’s more like a bugle blast announcing a cavalry charge; or a fanfare announcing the approach of royalty. And then the drums hit like God’s hand slapping earth. This is Motown. All of it: the celebratory swing, the surge and then the soar, the scientifically calibrated precision of every atom of every element in the song, the open invitation to everyone, everywhere, everytime, to get down and boogie, no matter race, color or creed. Berry Gordy’ll take all-a y’all’s money. The song is a Dantean beatific vision, a Paradiso set in 1960s America, where peace, love and understanding stopped being funny for just a moment and everybody beat their swords into plowshares and their plowshares into mirror balls. I’m a child of boomers, and we have to make fun of the 60s, because goddammit they didn’t live up to the promise of this song. Can’t forget the Motor City. For the space of two minutes and forty seconds, there is no God but Motown, and Martha Reeves is His prophet.

001. The Beatles “Help!”

(John Lennon/Paul McCartney)

1965

Available on Help!

John Lennon once said that there were only ever two songs he wrote as a Beatle of which he meant every word. They were “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Help!” He was probably taking the piss.

This was the first Beatles song I ever consciously heard. That’s why.

Next: Postscript. >>