The 100 Greatest Songs of the 1970s, Part XVII.

020. Yes “Roundabout”

(John Anderson/Steve Howe)

Fragile, 1972

Name one other prog-rock epic you can dance to. And I don’t mean tap your toes, sway groovily, or execute a stately pas de deux. I mean dance — ass shaking, feet moving, and on the “in and out of the lake” breakdowns you can actually headbang if you’ve a mind to. Chris Squire’s knotty, heavy bass playing is as funky as Bootsy Collins or Larry Graham, Bill Bruford rocks mightily on the kit, and even Rick Wakeman — yes, Rick Wakeman — acquits himself with some Bernie Worrell-esque flashes of genius on the organ. And then there’s Steve Howe and Jon Anderson. Howe is competent enough — his acoustic picking on the downbeat section verges on the beautiful — but Anderson is at best an acquired taste, and it’s actually a compliment to say that he doesn’t (and perhaps can’t) ruin this song. Anyway. Progressive rock, in its ideal form, was supposed to take rock music into conceptual and harmonic territories that only compositional (classical) and jazz music had previously broached; its failure was twofold: first, no progressive band was as intelligent or forward-thinking as the leading composers and jazz musicians of the time, and second, rock & roll is an unsteady footstool to pile towering structures upon. Prog was best when it ignored the conceptual hooey and went (like all great rock) for the jugular. Like this.

019. Johnny Thunders “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory”

(Johnny Thunders)

So Alone, 1978

A jet boy in a beaten age, the scruffiest and most forlorn New York Doll never fulfilled the promise of his best work, and became just another junkie casualty in the unrocking ’90s. He made several valiant attempts after the implosion of his original band, though, spitting up a gloriously noisy Heartbreakers album in 1977 (casually bridging the distance between New York punk and London punk, not to mention their roots in good old rock & roll), and then released a more measured, wary solo record a year later, on which appeared the finest and most heartbreaking punk ballad ever written or recorded. That’s not an oxymoron: one favorite meaning of punk is “stripped down to essentials,” and for fifteen years of wildly uneven concerts he usually played this song solo on acoustic guitar. This original album version isn’t quite as shatteringly or beautiful as most live versions you can find; it’s overproduced, tries too hard to rock, and goes on too long. But Thunders was nothing if not adaptable; he makes it work, using his trademark bleeding-fuzz solos to underscore the pain and longing in the verses, and when the chorus kicks in over a drum line adapted from “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the stark simplicity of the lyrics can always kick you in the gut no matter how many overdubs there are. If you don’t know the song, listen to this version first, but then find a live version to fall in love with, L-U-V.

018. The Commodores “Easy”

(Lionel Richie)

The Commodores, 1977

How the mighty have fallen: Lionel Richie is today best known as the father of a certain unecessary celebrity. Conan O’Brien does jokes where “Lionel Richie” is the punchline. And even before all that, he was most famous for being a soupily bland sweater-wearing ballad singer in the 80s, a cross between Billy Ocean and Bobby McFerrin. How the mighty had fallen, even then. But from the beginning it was not so; the Commodores were one of the truly great funk/soul bands of the latter half of the 1970s. “Brickhouse” mostly gets played at weddings these days (wait, at weddings? Yes, at weddings), but its unstoppable dancefloor majesty is the equal of anything by Earth, Wind & Fire or Kool & the Gang. (Speaking of the fallen mighty . . . .) But it’s on this soulful ballad, which was intentionally — and successfully — written to try to top the r&b, pop, adult contemporary and country charts at once (though the country charts were only topped by a cover of it), that the Commodores really nailed it. From its lazily funky piano line to the smooth, pillowy horns, to the country swing of the rhythm, given a glossy urban makeover in the production but unable to hide its roots, it’s pitch-perfect and elementally satisfying. Even the fuzzed-out guitar solo is bliss; and Richie himself proves that once upon a time he could really sing. How great is a song when not even a Faith No More cover can ruin it?

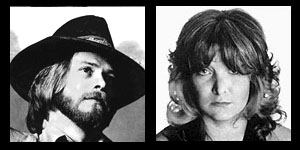

017. John Baldry & Maggie Bell “Black Girl”

(Huddie Ledbetter)

It Ain’t Easy, 1971

For about five years there — say 1968 to 1972 — white British rockers were obssessed with the music on scratchy old 78s, the blues and early country and folk and jug-band music represented most often by Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. Obsessed not only with that music, but with covering it, with getting their sound as close as possible to the wild, woolly original, but also without pretending the last thirty years hadn’t taken place. The Rolling Stones probably did it best most often, but any number of acts tried their hand at it — and often managed something quite listenable. John Baldry, though, had better credentials than most; he’d been playing the blues in England longer than just about anyone besides Alexis Korner. Just about anyone who was anyone had played in his band (including most of the Rolling Stones and two-thirds of Cream), and he had a great craggy voice. After years spent in the smarm-pop wilderness of late-60s London, he was revitalized by an amazing, rootsy record that was equally produced by Rod Stewart and Elton John. For the second track, Stewart roped in fellow Scot and Stone the Crows vocalist Maggie Bell to duet with Baldry on Leadbelly lyrics. The tune is usually more familiar as bluegrass standard “In the Pines,” but here it can chill your blood, especially when Maggie lets loose one of her astonishing banshee screams. And Rod’s house band from his brilliant initial period, particularly Sam Mitchell on slide guitar, tear it up.

016. The Temptations “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today)”

(Barrett Strong/Norman Whitfield)

single, 1970

In late 2005, not many weeks apart, I saw the Neville Brothers cover this song twice: once on Conan, and once on Leno. They were amazing, revitalized and given a furious urgency by Hurricane Katrina and the government’s horrifically inadquate response to it. But the real star was the song itself. I’d venture to bet that no other thirty-five-year-old protest song has aged as well, or is more heartbreakingly timely, than this one. (And it probably always will be, as long as humanity lasts.) The Temptations were the greatest black group in the world at the time, and had successfully negotiated the culture shifts of the late 60s by radicalizing their lyrics and cinema-funking their sound; Norman Whitfield is one of the more unheralded geniuses of the age. It opens with hoarse, distant shouts of “One two three four” and bubbling psychedelic guitars, but the tense tenor of the verses turn over to turbo-polished hard funk as the chorus is shouted in unison — and the horns get to play jazz-funk in the interstices. It’s a riveting song, searing in its catalogue of modern miseries but epically hopeful too (ah, Motown). But the best time to listen to it, I’ve found, is in my car with the windows rolled up, turned up as loud as my speakers can manage, so I can beg, scream and shout along with the lyrics. When it gets to “people all over the word are shouting end the war,” I choke up. Every single time.

Next: 015-011. >>

No comments:

Post a Comment